The Contemporaries Series

Bond: Special Agent

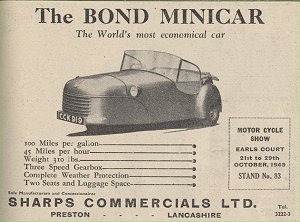

Figure 1. Recent biography

Introduction

The editors have considerable respect for Laurie Bond and are pleased to offer this article which examines his work and designs.

He was a capable engineer, amateur racing driver, entrepreneur; reading demand, marrying product with defined client.

He capitalised on skills, diversified when it seemed opportune.

He contributed to Britain’s growth, change and improvement through the Austerity to Affluence era of post war Britain

He ought to be given credit for his manufacturing capacity, the sustainability of his products and the fact he extrapolated 2nd World War technologies into his products and may have influenced Chapman.

Laurie Bond is a very significant Industrial Designer.

He is not as famous as Chapman but both men had much in common.

We shall explore the commonality in this article.

Bond did much to motorise and mobilsed Britain in the post war era and perhaps deserves more credit than has been given.

It’s also possible that he helped inform Chapmans ideas for the Elite and Type 25.

Laurie Bond 1907-1974 was mature person in the important post war era as the summary indicates

1945-age 38

1947-age 40

1957-age 50

1974- died at age 67

Economic context to 1950’s

Subscribers might like to see our dedicated articles on the 1950’s in which we offer statistics relating to income in order to better understand customer affordability and the financial discipline; the design / entrepreneurs faced bringing them the products they required.

Subscribers might like also to explore major socio-economic events impinging on the 1950’s which include The Suez Crisis, the development of the motor cycle and sidecar for family transport, demographics, mass production, the impact of credit /deferred terms /Hire purchase

The following statistics from the net are useful: –

“In 1950, the UK standard of living was higher than in any EEC country apart from Belgium. It was 50% higher than the West German standard of living, and twice as high as the Italian standard of living. By the earlier Seventies, however, the UK standard of living was lower than all EEC countries apart from Italy (which, according to one calculation, was roughly equal to Britain). In 1951, the average weekly earnings of men over the age of 21 stood at £8 6s 0d, and nearly doubled a decade later to £15 7s 0d. By 1966, average weekly earnings stood at £20 6s 0d.[201] Between 1964 and 1968, the percentage of households with a television set rose from 80.5% to 85.5%, a washing machine from 54% to 63%, a refrigerator from 35% to 55%, a car from 38% to 49%, a telephone from 21.5% to 28%, and central heating from 13% to 23%.[202]

Between 1951 and 1963, wages rose by 72% while prices rose by 45%, enabling people to afford more consumer goods than ever before.[203] Between 1955 and 1967, the average earnings of weekly-paid workers increased by 96% and those of salaried workers by 95%, while prices rose by about 45% in the same period.[204] The rising affluence of the Fifties and Sixties was underpinned by sustained full employment and a dramatic rise in workers’ wages. In 1950, the average weekly wage stood at £6.8s, compared with £11.2s.6d in 1959. As a result of wage rises, consumer spending also increased by about 20% during this same period, while economic growth remained at about 3%. In addition, food rations were lifted in 1954 while hire-purchase controls were relaxed in the same year. As a result of these changes, large numbers of the working classes were able to participate in the consumer market for the first time.

The significant real wage increases in the 1950s and 1960s contributed to a rapid increase in working-class consumerism, with British consumer spending rising by 45% between 1952 and 1964.[207] In addition, entitlement to various fringe benefits was improved. In 1955, 96% of manual labourers were entitled to two weeks’ holiday with pay, compared with 61% in 1951. By the end of the 1950s, Britain had become one of the world’s most affluent countries, and by the early Sixties, most Britons enjoyed a level of prosperity that had previously been known only to a small minority of the population.[208] For the young and unattached, there was, for the first time in decades, spare cash for leisure, clothes, and luxuries. In 1959, Queen magazine declared that “Britain has launched into an age of unparalleled lavish living.” Average wages were high while jobs were plentiful, and people saw their personal prosperity climb even higher. Prime Minister Harold Macmillan claimed that “the luxuries of the rich have become the necessities of the poor.” Levels of disposable income rose steadily,[209] with the spending power of the average family rising by 50% between 1951 and 1979, and by the end of the Seventies, 6 out of 10 families had come to own a car.[210]

Car ownership rose by 250% between 1951 and 1961, and between 1955 and 1960 average weekly earnings rose by 34%, while the cost of most technological consumer items fell in real terms. In the 1950s consumers had more money to spend on goods, and more goods from which to choose.”

The Contemporaries Series has been written to achieve the following objectives: –

- To compare and contrast the designs, products and achievements of Colin Chapman/Lotus with their, rivals, contemporaries, peers and competitors

- To benchmark achievement by a series of consistent criteria

- To extract from the comparisons an objective assessment

- To counterpoise some specific models against each other

- To examine the nature, culture and economic viability of the British specialist sports car market.

The British specialist car market has been extremely vulnerable to economic downturn and its history is littered with casualties. Those that have survived are worthy of examination.

Please note the editors have striven to achieve objectivity and consistency of comparison throughout however it will be appreciated with many conflicting sources, references and specifications this is not an easy task and some inaccuracies may occur. We are happy to correct these presented with reliable alternatives.

Subscribers might like to see further complementary and structured A&R articles: –

- Morgan

- Marcos

- Ginetta

- Gilbern

- Berkeley

- Vespa

- Formula Junior

- Design Heroes series including Frank Whittle, R&L Day, Ernst Race

Bond Biography from wiki and net: –

“Lawrie” Bond Lawrence (2 August 1907 – September 1974) was a British engineer and designer noted for designing several economical and lightweight vehicles, amongst which were the Bond Minicar, the Berkeley and the Bond Equipe GT[1]

Bond was born in Preston, Lancashire on 2 August 1907.[1] His father was Frederick Charles Bond, a local historian and artist.[1] After attending Preston Grammar School, Bond worked for a variety of engineering firms, notably the Blackburn Aircraft Company during the second world war.[1] He then went on to enjoy modest success as an amateur racing driver and racing car designer utilising knowledge he had gained in the aircraft industry in lightweight, stressed skin construction. In 1948 he designed a small three-wheeled car for road use and the attention this gained in the media highlighted the design’s commercial potential and provided the basis for the Bond Minicar.[2]

In later life Bond ran a pub near Bowes in North Yorkshire where he combined the role of freelance designer with that of publican. Later, ill health resulted in a return to Lancashire, to Ansdell, where he died in September 1974, aged 67.[2]

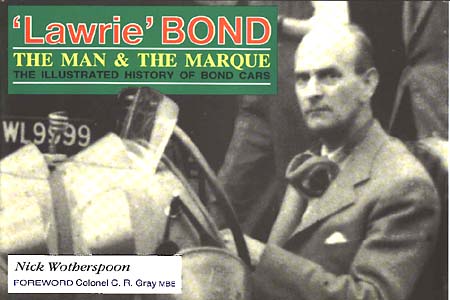

Figure 2. Early motorcycle/scooter

Bond Bikes

Bond designed a series of motor bikes and scooters .It’s possible these were influenced by the success of the Italian Vespa [see A&R dedicated article]

Minibyke of 1949, this was quite a radical concept and specification included: –

- Priced at £55 plus £14-7-0 PT in 1950

- Prototype weight 90 lb. [see images on net of Laurie holding the bike

- Villiers 1F engine 98cc

- 35-40 mph cruising speed

- 200 mpg

- 520 built

Bond Type C racing car

Wotherspoon:-

Bond weighed less than 400 lb.

500cc F500 car.Retailed at £585 +3163/5s PT

Bond Cars

Bond from Jenkinson: –

“Laurie Bond is a fanatic for small lightweight vechicles , his production three wheelers being well –known .Occasionally he made sorties into the racing world , mostly hill climbs , and invariably proved certain ways not to build racing cars …….another front wheel drive effort that came to nothing was his formula junior car “

“It was a small beginning for the innovative Bond Company, and became something of a modest success, despite possessing what many people today would consider to be a sub-entry level specification. Between the appearance of the first prototype in 1948, and the end of its production run in 1966, a not insubstantial total of 26,500 were produced – and it was this success that paved the way for enough profitability to create the Equipe.

The industrial powerhouse behind the Bond name was based in Ribbleton Lane, Preston. Overseen by Sharp’s Commercials, the producer of Lawrie Bond’s Minicar, was a part of the Loxhams and Bradshaw industrial conglomerate. Although the company’s core business was a long way removed from the day-to-day business of building these micro-cars, it remained very much in charge, right up to the 1964, when Lawrie’s company became the much more important-sounding Bond Cars Limited.

However, come 1968’s take-over of Loxhams & Bradshaw by dealer group Dutton-Forshaw, Bond Cars ended up being sold to Tamworth-based Reliant.”

Bond from wiki edit

“The basic concept for the minicar was derived from a prototype built by Lawrence “Lawrie” Bond, an engineer from Preston.[3] During the war, Bond had worked as an aeronautical designer for the Blackburn Aircraft Company[4] before setting up a small engineering business in Blackpool, manufacturing aircraft and vehicle components for the government. After the war he moved his company to Longridge where he built a series of small, innovative racing cars, which raced with a modest amount of success.[3] In the early part of 1948, he revealed the prototype of what was described as a new minicar to the press.[5]

Described as a “short radius runabout, for the purpose of shopping and calls within a 20-30-mile radius”, the prototype was demonstrated climbing a 25 per cent gradient with driver and passenger on board. It was reported to have a 125 cc (8 cu in) Villiers two-stroke engine with a three-speed gearbox, a dry weight of 195 pounds (88 kg)[6] and a cruising speed of around 30 mph (48 km/h). At the time of the report (May 1948), it was stated that production was “expected to start in three months’ time”.[7] The prototype was built at Bond’s premises in Berry Lane, Longridge where it is now commemorated with a blue plaque.[8]

Sharp’s Commercials was a company contracted by the Ministry of Supply to rebuild military vehicles.[9] Knowing that the Ministry were ending their contract in 1948, and recognising the limitations of his existing works as a base for mass production, Bond approached the Managing Director of Sharp’s, Lt. Col. Charles Reginald ‘Reg’ Gray, to ask if he could rent the factory to build his car. Gray refused, but said that instead, Sharp’s could manufacture the car for Bond and the two entered into an agreement on this basis.[10] Bond carried out some further development work on the Minicar, but once mass production was underway, left the project and sold the design and manufacturing rights to Sharp’s.[11]

The engine bay of a 1959 Minicar Mark F. The kick start on the right hand side of the engine was fitted for emergency use; all Minicars were started from the driver’s seat.[12]

The prototype and early cars utilised stressed skin aluminium bodywork, though later models incorporated chassis members of steel.[12] The Minicar was amongst the first British cars to use fibreglass body panels.[13]

Though retaining much of Lawrie Bond’s original concept of a simple, lightweight, economical vehicle, the Minicar was gradually developed by Sharp’s through several different incarnations. The majority of cars were convertibles, though later, hardtop models were offered, along with van and estate versions. Minicars were generally available either in standard or deluxe form, though the distinction between the two was largely one of mechanical detail rather than luxury. The cars were powered initially by a single-cylinder two-stroke Villiers engine of 122 cc (7 cu in). In December 1949 [14] this was upgraded to a 197 cc (12 cu in) unit. The engine was further upgraded in 1958, first to a single-cylinder 247 cc (15 cu in) and then to a 247 cc (15 cu in) twin-cylinder Villiers 4T. These air-cooled engines were developed principally as motorcycle units and therefore had no reverse gear. However, this was a minimal inconvenience, because the engine, gearbox and front wheel were mounted as a single unit and could be turned by the steering wheel up to 90 degrees either side of the straight-ahead position, enabling the car to turn within its own length.

A method of reversing the car was offered on later models via a reversible Dynastart unit. The Dynastart unit, which doubled as both starter motor and dynamo on these models incorporated a built-in reversing solenoid switch. After stopping the engine and operating this switch the Dynastart, and consequently the engine, would rotate in the opposite direction.[15]

Tax position

Tax advantage editThe car proved popular in the UK market, where its three-wheel configuration meant that it qualified for a lower rate of purchase tax, lower vehicle excise duty and cheaper insurance than comparable four-wheel cars. The three-wheel configuration, low weight and lack of a reverse gear also meant that it could be driven on a motor cycle licence.

Tax changes[edit]

In April 1962 the purchase tax rate of 55 percent, which had been applied to all four-wheeled cars sold in the UK since the war was reduced to 45 per cent.[16] In November 1962, it was reduced by another 20 per cent to 25 per cent – the same rate as that applied to three-wheelers. This rapid change meant that at the point of sale, some three-wheelers became more expensive than four-wheeled cars like the Mini. In response, Tom Gratrix, head of Sharp’s sent a telegram to the Chancellor warning that unless a similar tax cut were given to the purchase tax rate for three-wheelers, there would be 300 redundancies and possibly the closure of the Sharp’s factory.[17] No cut was forthcoming, sales of Minicars declined rapidly from this point and the final Minicar was produced in 1966.[18] At the end of production 24,482 had been made.[19]

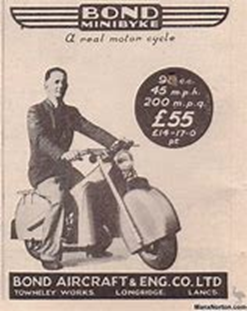

Minicar 1949–51[edit]

Sold as the Bond Minicar (the Mark A suffix being added only after the Mark B was introduced),[20] the car was advertised as the world’s most economical car.[21] It was austere and simple in design, without luxuries.[12] Production began in January 1949,[14] although 90 per cent of the initial production was said to have been allocated to the overseas market.[22]

As with the prototype, a large proportion of the Minicar was made from different aluminium alloys. The main body was a very simple construction of 18 swg sheet with a 14 swg main bulkhead.[23] The integrity of the main stressed skin structure was enhanced by the absence of doors, the bodysides being deemed low enough to be stepped over without major inconvenience (unless you were wearing a skirt).[24] Most of the bodywork panels were flat or fairly simple curves whilst the compound curves of the bonnet and rear mudguard arches were pressed out as separate panels. The windscreen was made from Perspex.[14] The car was alleged to weigh only 308 pounds (140 kg) “all-in”[23] or 285 pounds (129 kg) dry[25] and its light weight was regularly demonstrated by one person lifting the entire rear end of the car off the ground unaided.[26][27] A test run between Preston and London at an average speed of 22.8 mph (36.7 km/h) gave an average fuel consumption of 97 mpg‑imp (2.9 L/100 km; 81 mpg‑US) for the journey.[25]

The car had a single bench seat with a small open compartment behind suitable for luggage. There was also a fold-down hood with detachable side screens.[24] The headlights were separate units mounted on the side of the car,[28] though of such low output, they have been described as providing “more of a glimmer than a beam”.[29] At the rear there was a tiny, single, centrally-mounted lamp.[30]

The air-cooled Villiers 10D 122 cc (7 cu in) engine had a unit construction three-speed manual gearbox without reverse.[14] This had an output of 5 bhp (4 kW; 5 PS) at 4,400 rpm which the manufacturers claimed gave a power-to-weight ratio of 49 bhp (37 kW; 50 PS) per ton unladen.[30] The engine unit sat in an alloy cradle ahead of the front wheel, together forming part of its support. Both front wheel and engine were sprung as part of the trailing link front suspension system, which was fitted with a single coil spring and an Andre Hartford friction damper.[23] The rear wheels were rigidly mounted to the body on stub axles with suspension provided by low pressure “balloon” type tyres.[12] Starting was achieved by using a pull handle mounted under the dash panel and connected by cable to a modified kick-start lever on the engine.[14] The steering comprised a system of pulleys and a cable usually referred to as “bobbin and cable”,[12] connecting a conventional steering wheel to the front steering unit. The bobbin and cable steering arrangement was replaced by a rack and pinion system in October 1950.[14] Brakes were provided on only the rear wheels; they were conventional drum brakes operated by a system of cables and rods.[23] Early on, Sharp’s adopted a policy of continual gradual upgrading of the Minicars, either to simplify or reduce maintenance, to redress noted failings or to improve some aspect of performance. Such changes were usually made available as kits to enable existing owners to upgrade their own cars retrospectively.[30]

In December 1949, a Deluxe version was added to the range. This has a Villiers 6E 197 cc (12 cu in) engine, which had an increased output to 8 bhp (6 kW; 8 PS) and a power-to-weight ratio of 51 bhp (38 kW; 52 PS) per ton.[31] There were also a number of modest refinements including a spare wheel and a single wing mirror.[14] The manually operated windscreen wiper fitted on the standard car was upgraded to an electric Lucas type. Although this was found to damage the original Perspex windscreen,[30] it was not replaced by a Triplex Safety Glass screen until the introduction of the Mark B in 1951.[14][32]

A Bond Minicar Deluxe tested by The Motor magazine in 1949 and carrying only the driver had a top speed of 43.3 mph (69.7 km/h) and could accelerate from 0-30 mph (48 km/h) in 13.6 seconds. A fuel consumption of 72 mpgimp (3.9 L/100 km; 60 mpgUS) was recorded. The test car cost £262 including taxes.[24]

Towards the end of 1949 (as unveiled and demonstrated in October at the Motor Cycle Show at Earls Court, London) an optional mechanical reversing device became available which comprised a long lever with a ratchet and a hexagonal socket on the end which fitted onto the centre of the driver’s side rear wheel hub. This device could then be operated from the driving seat and allowed the car to be cranked backwards by hand to assist with maneuvering.[30]

|

|

| Sole manufacturers and Concessionaires

SHARPS COMMERCIALS LTD Preston – Lancashire Tel 3222-3 |

Figure 3. Early brochure image from net

The Type C Bond was a very light car at under 400 lbs. It was of an aluminium construction. We believe it was of semi-monocoque construction. The engine was a 122 cc Villiers and estimated fuel consumption was 104mpg. It was termed as “Shopping Car “and this indicates the market research and customer base identified which was not inconsiderable.

Bond Formula Junior

| Marque | Bond |

| Model | Formula Junior |

| Date | 1960 |

| Engine | Ford Cosworth 105 E [forwards & back to front] |

| No.cylinders/capacity | 4 cylinders, 997 cc |

| Bore and stroke | 80.96 x 48.41 mm |

| Max.bhp | 80 at 7,200 rpm |

| Carburetters | 2 twin choke Weber 38 DC03 |

| Battery | 12 volts |

| Suspension: front | independent by coil spring /damper units and wishbones |

| Suspension: rear | low-pivot swing axle with coil spring/damper units |

| Brakes | Girling 9″ x 1.75″ integral Bond drums, outboard f&r |

| Steering | Rack and pinion |

| Wheels | Bond cast iron, bolt on |

| Clutch | single dry plate |

| Gearbox | Ford Anglia 4-speed |

| Final drive | Bond unit incorporating Ford crown wheel & pinion to front wheels |

| Frame & body | body and frame one single stressed skin unit based on g/f reinforced |

| Weight | just over 100 lb. |

| Wheel base | 7ft-3in |

| Length | 11ft-10in |

| Height | 3ft-2in |

| Track: front | 3ft-10in |

| Track: rear | 3ft-11in |

| Kerb weight | 796 lb. |

| Ground clearance | 5in |

Roberts: –

“Laurie Bond’s design for the Formula Junior car differs a good deal from the normal, particularly as it has front wheel drive and a forward power unit which is mounted back to front and fairly well back from the radiator. The Bond car is designed mainly for the FJ enthusiast who wants reliability with minimum costs and maintenance”

Wotherspoon:-

Bond

Bond Equipe from wiki: –

“The original Equipe, the GT, was based on the Triumph Herald chassis with a fastback fibreglass body and also utilised further Triumph parts including the windscreen / scuttle assembly, and doors. The September 1964 GT4S model saw revisions to the body with twin headlights and an opening rear boot. It was powered by the same, mildly tuned up (63 bhp, later increased to 67 bhp), Herald-based 1147 cc engine used in the Triumph Spitfire.

The engine was switched to the 75 bhp (56 kW) 1296 cc Triumph Spitfire engine in April 1967, just one month after the Spitfire itself had undergone the same upgrade,[3] the revised model being identified as the GT4S 1300.[4] An increase in claimed output of 12% resulted.[4] At the same time the front disc brakes were enlarged and the design of the rear suspension (one component not carried over unmodified from the Triumph Spitfire) received “attention”.[4]

The GT4S was joined by the 2-litre GT with a larger smoother body directly before the London Motor Show in October 1967.[5] This model was based on the similar Triumph Vitesse chassis and used its 1998 cc 95 bhp (71 kW) six-cylinder engine. The 2-litre GT was available as a closed coupé and, later, as a convertible. The car was capable of 100 mph (161 km/h) with respectable acceleration. Horsepower and suspension improvements were made in line with Triumph’s Mark 2 upgrade of the Vitesse in Autumn 1968, and the convertible was introduced at the same time.

Production[edit]

- Bond Equipe GT 2+2: April 1963 – October 1964; 451 (including 7 known pre-production cars)

- Bond Equipe GT 4S: September 1964 – January 1967; 1934

- Bond Equipe GT 4S 1300: February 1967 – August 1970; 571

- Bond Equipe 2-Litre Saloon: January 1967 – January 1970; 591

- Bond Equipe 2-Litre Convertible: January 1968 – January 1970; 841

Total Equipe Production = 4389 (including one known Mk.3 prototype made at Tamworth)[6]

Production ended in August 1970 when Reliant, which had acquired Bond in 1969, closed the factory.”

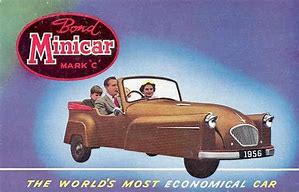

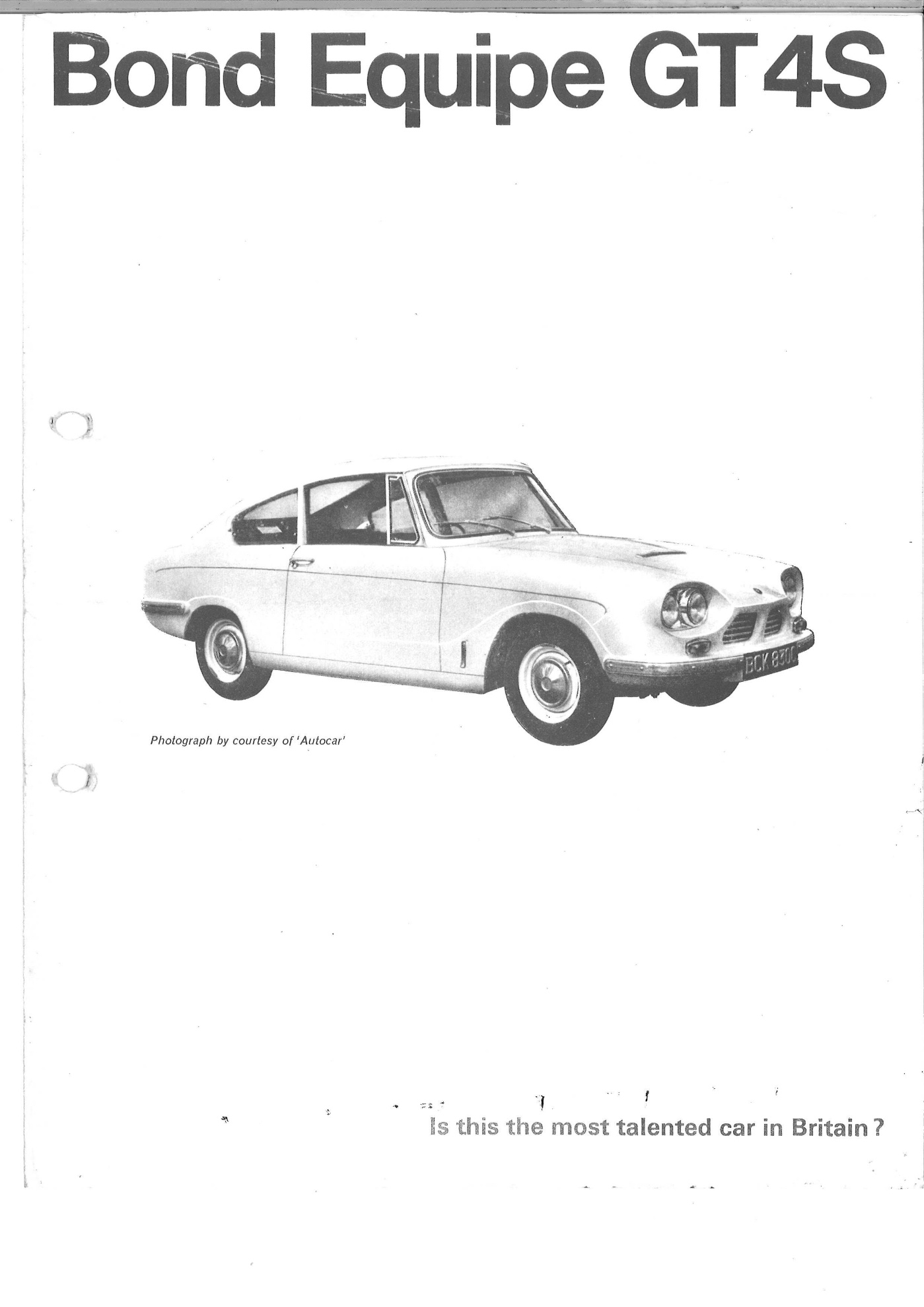

Figure 4.Sales brochure A&R collection

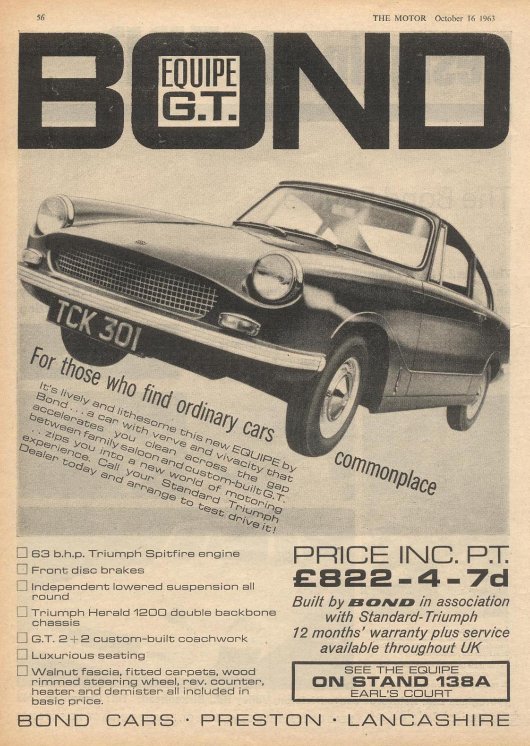

Figure 5.The Motor ,1963 note price .A&R collection

Watkins: –

“The Preston, Lancashire firm of Bond Cars built closed sports coupes using Triumph mechanical components during the sixties. ……..a more powerful version used the 6-cylinder , 104 bhp 2 –litre power unit from the Triumph GT6 , for which a top speed of close to 100 mph was claimed …………..bodywork was of glassfibre , and permitted a relatively light weight for these well-equipped if ungraceful cars .the 2-litre model was available in convertible form .

The Bond Equipe GT4S 1300 with Spitfire power unit developing 75 bhp from its 1296 cc provided performance close to that of the Triumph Spitfire but offered, in addition full four seat accommodation.

Tech spec from Manwaring: –

| Marque | Bond |

| Specification | GT 4S Sport Saloon |

| No. of Cylinders | 4 [Triumph] |

| Cubic Capacity | 1147cc |

| Compression Ratio | 09:01 |

| BHP | 63 |

| Max. mph | 63 |

| Overall length | 13ft.-1 1/2in |

| Overall width | 5ft. |

| Height | 4ft-5in |

| Wheel base | 7ft.-7 1/2 in |

| Track [front] | 4ft. |

| Track [rear] | ditto |

| Weight [dry] | 14.5 cwt |

| Turning circle | 25ft |

| Fuel tank capacity | 10 imp gals |

Commonality

There are degrees of commonality between Bond and Chapman /Lotus.

On this occasion the editors have been unable to find a set of consistent marque specification comparisons and have therefore relied on several sources. For general consistency the editors use Taylor, The Lotus Book. In this article other additional/ complementary sources are used and stated where appropriate.

Brief Company Histories and Design Methodologies

Lotus

It’s not considered necessary here to recall Chapman / Lotus history in great detail. Much can be discovered by the comparison of commonality given above and in -depth analysis can be found in A&R articles: –

- Lotus Design Decades

- 20c Motoring Icons

For this article’s objective Chapman/Lotus history [non-chronological] might be summarized as: –

- Chapman’s history and development witnesses some extreme polarization of success and fortune in both commerce and competition. Chapman is said to have been eulogized and demonized in equal measure

- Chapman delivered a succession of FI cars and won 7 World Constructors Championships .Following an interruption after his death Lotus is again currently in the forefront of FI which have been complemented with equally distinctive high performance road cars notably the Elite,Elan,Esprit etc.

- Lotus cars successfully competed at nearly every branch and level of motorsport and introduced some of the greatest British drivers to FI

- Chapman’s designs were invariably innovative, ground breaking and iconic

- Chapman placed importance on research & development and consultancy that sometimes carried the organization and possibly subsidized it.This principle has continued to the present day.

- Chapman is renowned for his collaboration with the likes of Ford [cars and engines- Cortina, Twin Cam and Cosworth DFV], and Vauxhall [ Talbot Sunbeam Lotus / Carlton Omega]

- Chapman for all his flaws developed talent and developed human potential

- Chapman had a reputation as a ruthless entrepreneur and through DeLorean was found guilty of fraud

- Since his death in 1982 Lotus has suffered multiple changes in ownership, financial difficulties but despite this has still produced the award- winning Elise that almost twenty years after its introduction still achieves plaudits and remains incontestable in its class; and with build quality issues in the main resolved.

- Chapman with his colleagues and engineers contributed much to post war Britain’s reputation as the leader in International motor sport.

- The Chapman design methodology continued in the Elise is innovation, experimentation, performance through light weight / high power to weight ratios, sheer unalloyed driving pleasure and satisfaction.

Business Philosophy

We have outlined this in other A&R articles and some aspects are listed above.

As noted, Bond had some similarity/ commonality with Chapman and Lotus.

The Bond Owners Club website is worth visiting for the comprehensive and comparative nature of its survey on Bond, his design and manufacturing. See: –

http://www.bondownersclub.co.uk/

In brief summary these are some of the products Bond and his companies undertook. Note the Bond website importantly also records production volumes – which of course reflects on demand, relative take up, profitability etc.

- Minibyke

- Sharp Commercial vechicles

- Unicycle

- P1 & P2 scooters

- Sea Ranger [boat]

- Power ski

- Trailer tent

- Trek tent

- Suitcase [ actual car storage]

- Scooter ski

- Car accessories additional to those listed here

Colin Chapman

Possibly the quotation that most encapsulates Chapman design methodology is by Rudd: –

“The most elegant and effective and traditional Lotus solution is the one with the least parts effectively deployed”

This was design mantra that permeated his road and competition cars. It brought him international success through British Club Racing to Indianapolis, Le Mans and seven FI Constructors championships.

The philosophy of Chapman relating to manufacturing cars is complex. He started in a humble fashion with limited resources but considerable ambition and the application of innovation to overcome limited resources.

Success led to him offering services and with the Lotus MK.VI low scale production. The Mk.VI sold approximately one hundred cars in the early mid 1950’s which the editors believe established Chapman both competitively and commercially. These “kits” were for the enthusiast and club racer. At the same time Chapman was developing the aerodynamic racers which were far more expensive, sophisticated with racing engines.

It’s not known categorically if Chapman built cars just to support racing but they did provide finance. To this ends he designed cars for particular racing classes. Overlapping were the road cars like the Elan, Europa. Some of the cars were over ambitious and lacking development and quality control. [This was probably a function of the idealist/ engineering integrity specification overcoming available budget and volume – of course some would argue a proper business plan would have revealed this.

Chapman enjoyed considerable success with collaboration with other manufacturers namely Ford and Talbot.

In the 1970’s he could see that taste, times and expectation was changing and along with VAT the market for the enthusiast kit car such as the Seven was barely viable. He hived it off.

Chapman tried to take the Lotus brand up market through the 1970’s and 80’s but this was not an entire success partly because the product was not the most competitive but perhaps more so the world economy and crisis associated with oil. However, the Esprit became iconic as a result of its appearance in James Bond.

Chapman was willing to diversify and this can be seen in theory to be desirable but in practice it was not a commercial success e.g. Furniture, boats and micro lights.

Chapman was implicated in DeLorean. Against the background of other events we might understand the temptation and feelings of injustice but these are not an excuse.

More recently with stability from Proton Lotus has found international success with the Elise [and this is perhaps it’s true to the Chapman methodology and a car suitable for the enthusiast pure driving experience] and improved build quality, reliability etc. Lotus is doing well again in FI

It ought to be appreciated that virtually all Chapman are designs are essentially green because of their superior mechanical efficiency ensured through low weight and aerodynamics.

Chapman extracted considerable income from consultancy and this applies up to the present time.

Profitability Spreadsheet

The editors have been unable to find source information that is reliable and comparable between the two companies and product ranges. As a guide the production volumes and sales prices of respective manufacturers might be extrapolated.

Brief insight is provided of the eras the two organisations overlapped.

Lotus

For Lotus there are few direct references to annual returns however the Lotus Book by William Taylor gives useful information on production numbers and Nye supplements this with some accounts. Financial information for Lotus is not readily available although the A&R have traced some, this will be the basis for an extended article. For our purposed here it will be sufficient to quote Nye.

We understand the following figures applied for Lotus: –

- 1959 Loss £29,062

- 1964 Profit £113,000 [nb Elan production 1195]

- 1965 [nb 2505 cars including 986 Lotus Cortina’s]

- 1966 £251,000 on turnover of £2,156,000

- 1968 At Hethel Lotus Group profitability had increased by 11.5 to 16.5 % and production 1968/69 is suggested at 4506

- 1970 Profitability dropped to 6.5%

- 1980 365 cars built and around this period at its lowest ebb Lotus was valued at only £3m

Lawrence has stated: –

“At the end of 1963 Lotus …… a total of 1, 1195 Lotus cars of all types were made. On top of that were 567 Lotus Cortina’s. The turnover was £1,573,000…. and generated a pretax profit of £113,000.The financial figures to not take into account the money generated by Team Lotus , which was paid into the account of Team Lotus Overseas.

Using just one example of race winnings [which is not entirely reliable or representative] we can note that the winnings from the 1966 Indianapolis was $ 77,000 approximately.

Subscribers may wish to bring these statistics up to-date using current information from the net. We shall not record it here because of the dating aspect.

Weights

Weight is a particular good measure of assessing fuel efficiency. Unfortunately, we don’t have comparable cd information for both marques to make reliable and consistent comparisons.

The respective weights provide interesting comparisons; particularly when the same engine / gearbox and rear axle might have been used in both marques.

| Year | Marque | Model | Weight | lbs./ cwt | |

| 1948 | Lotus | Trials Car | 1092 | lbs. | |

| 1951 | Lotus | Mk.III | 815 | lbs. | |

| 1952 | Lotus | Mk.VI | 952 | lbs. | |

| 1957 | Lotus | Seven | 924-980 | ||

| 1968 | Lotus | Seven | 1210-1258 | ||

| 1954 | Lotus | Mk.VIII | 1148 | ||

| 1956 | Lotus | Eleven | 1019 | ||

| 1957 | Lotus | Elite | 1484 | ||

| 1962 | Lotus | Type 23 | 884 | ||

| 1962 | Lotus | Elan | 1210-1250 | ||

| 1962 | Lotus | Cortina | 1822 | ||

| 1966 | Lotus | Europa | 1350- | ||

| 1967 | Lotus | Elan +2 | 1180-1970 | ||

| 1969 | Lotus | Seven S iV | 1276-1310 | ||

| 1974 | Lotus | Elite | 2240-2550 | ||

| 1975 | Lotus | Elcat | 2450 | ||

| 1976 | Lotus | Esprit | 2218 | ||

| 1982 | Lotus | Excel | 2507 | ||

| 1989 | Lotus | Elan | 2198 | ||

| 1989 | Lotus | Carlton | 3641 | ||

| 1996 | Lotus | Elise | 1518 | ||

We have limited information on Bond, or Berkeley weights but where they have been published, we attempt to quote them.

Lotus v Bond –specific models

Here we examine two cars by the respective marques competing in the same era for potentially the same audience. For convenience and comparison information available from wiki has been adopted.

Bond Equipe :-

| Manufacturer | Bond Cars Ltd |

| Production | 1963-1970 4,389 made[1] |

| Assembly | Preston, UK |

| Body and chassis | |

| Class | Sports car |

| Body style | 2-door saloon 2-door convertible |

| Powertrain | |

| Engine | Triumph 1147, 1296 or 1998 cc |

| Transmission | 4-speed manual optional overdrive on 2 litre |

| Dimensions | |

| Wheelbase | 93 in (2,362 mm) [2] |

| Length | 160 in (4,064 mm) [2] |

| Width | 60 in (1,524 mm) [2] |

Lotus Elan +2 [wiki]: –

| Production | 1967–1975 |

| Assembly | Hethel, England |

| Designer | Ron Hickman |

| Body and chassis | |

| Body style | 2-door 2+2 coupé |

| Layout | Front-engine, rear-wheel-drive |

| Powertrain | |

| Engine | 1,558 cc Lotus TwinCam I4 (petrol) |

| Transmission | 4-speed & 5-speed manual (all-synchromesh) |

| Dimensions | |

| Wheelbase | 96.0 in (2,438 mm) |

| Length | 169.0 in (4,293 mm) |

| Width | 66.0 in (1,676 mm) |

| Height | 47.0 in (1,194 mm) |

| Curb weight | Approximately 1,960 lb (889 kg) |

Elan +2 and Bond Equipe Compared and Contrasted

Unfortunately, the editors do not have archive that test these cars by the same Road Test criteria. What we observe in general terms is that

Both cars: –

-

-

- Two -seater sports cars of light compact design, both moved to the plus 2 format –possibly to address growing families. Lotus might have sought to retain customer base and offer trade up

- Both bodies were made of fibreglass [but diametrically opposed structural concepts]

- The Bond was clever idea and sought to achieve production economics with economies of scale. However, they started to compete with mainstream sports saloons and even the Mini Cooper. The Lotus was reasonably expensive for the time and the probable clients being established professionals. [see A&R articles on Design Decades and social History –Price relativity.] In The Elan represented about 30% of a new house price.

- Production volumes were relatively low

- Note engines in respective cars

-

Product Prices

| c1952 | Lotus | Mk.VI | £400-500 | Estimated / specification | |

| Lotus | Eleven | £872 | £1308 inc pt | Ford 1172 sv | |

| Lotus | Eleven S2 | £1690 | pt£811 | Le Mans | |

| Lotus | Eleven S2 | £1490 | Nett | Club | |

| 1959/60 | Lotus | Seven S 1 | £892 | Eng’£356 | Chassis£499 |

| 1959 | Lotus | Seven S 1 | £1036 | “F” | |

| 1959 | Lotus | Seven S 1 | £1546 | “C” | |

| 1959 | Lotus | Seven S 1 | £536 | Kit form | Eng’options |

| 1960 | Lotus | Seven S 2 | £587 | Kit form | |

| 1961 | Lotus | Seven S 2 | £499 | Kit form | |

| 1962 | Lotus | Seven S 2 | £868 | ||

| 1962 | Lotus | Super Seven | £681 | pt£350 | inc cr gears |

| 1962 | Lotus | Super Seven | £599 | Kit form | without cr |

| 1965 | Lotus | Super Seven | £645 | Kit form | without extra |

| 1965 | Lotus | Super Seven | £695 | pt£173 | |

| c 1968 | Lotus | Seven S 3 | £775 | Kit form | |

| c 1968 | Lotus | Seven S 3 | £1250 | Kit form | SS Twin cam |

| 1969 | Lotus | Seven S 3 | £1600 | SS | |

| c1970 | Lotus | Seven S 4 | £895 | Kit form | |

| c1970 | Lotus | Seven S 4 | £1245 | Kit form | Twin cam |

| c1970 | Lotus | Seven S 4 | £1265 | Kit form | Holbay |

| c1973 | Lotus | Seven S IV | £1487 | ||

| 1963 | Lotus | Elite | £1451 | Kit form | Special Equip |

| c 1963 | Lotus | Elite | £1966 | inc-p’tax | |

| 1965 | Lotus | Elan | £1187 | £249 | |

| c1973 | Lotus | Elan Sprint | £2436 | ||

| 1971 | Lotus | Europa | £1595 | Kit form | Twin cam |

| 1971 | Lotus | Europa | £1715 | Twin cam | |

| c1973 | Lotus | Europa Spec | £2436 | ||

| 1983 | Lotus | Esprit S3 | £15380 | ||

| 1997 | Lotus | Elise | £20950 | 1.8i | |

| 2013 | Lotus | Elise | £29050 | 1.6 | |

| 2013 | Lotus | Elise | £37205 | 1.8S | |

| 2013 | Lotus | Evora | £53080 | 3.5 V6 | |

| 2013 | Lotus | Evora | £62290 | 3.5 V6S | |

| The Motor – Index to UK Prices – July 3, 1963[48] | ||

| Make/Model | Total (inc. taxes) | Kit |

| Lotus Elan 1500 | £1,317 | £1,095 |

| Lotus Elite Coupe | £1,662 | £1,299 |

| Lotus Elite Coupe (Special Equipment) | £1,862 | £1,451 |

| Lotus Seven Series II (Ford 109E) | N/A | £519 |

| Austin Healey 3000 Sports Convertible | £1,045 | N/A |

| Austin Mini Cooper S | £695 | N/A |

| Ferrari 250 G.T. Pininfarina Coupe | £5,606 | N/A |

| Ford Lotus Cortina | £1,100 | N/A |

| Make/Model | Total (inc. taxes) | Kit |

| Jaguar E-Type OTS | £1,828 | N/A |

| Jaguar E-Type F/H Coupe | £1,913 | N/A |

| M.G. Midget | £598[49] | N/A |

| M.G. B | £834 | N/A |

| Porsche 1600 Fixed Head Coupe | £1,900 | N/A |

| Porsche 1600-S90 Cabriolet | £2,527 | N/A |

| Triumph Spitfire 4 | £640 | N/A |

| Triumph TR4 | £906 | N/A |

Projected Futures

Bond ended in the late 1960’s we therefore make brief comment on Lotus

Lotus

Subscribers are directed to the net for precise up to date information. As this dates quickly we make generalised recent summary

Lotus has enjoyed considerable success and international acclaim with the Elise.

In 2002 Lotus were granted The Queens Award for Enterprise. In 2010 five new proposed models were introduced at the Paris Motor Show. These were to be released over a five-year period. This seemed to many somewhat over ambitious.

The recent range has included the Elise, Exige, and Evora.

The editors feel that the dilemma that surrounds Lotus is focused on its role. Lotus Consulting possible contribute deign to most of the cars in production today but these are invisible and my necessity secret. Its possibly also the greater source of income. The Lotus production models possible playing a promotional role and show case for the consultancy wing. Their economics partly assisted by shared components or related economies of scale. In absolute accountancy/ economic terms they may not be fully viable. Lotus as such cannot cross subsidize as larger manufacturers might across their range that might include commercial vehicles etc.

Lotus possibly also suffers from placement in the hierarchy of brands. Chapman realized that the economics of the enthusiast sports car was barely viable. He intentionally took the range up market. However, in the process reputations, quality, resale value, perception and value for money become critical. No longer in a defined niche competition with the major manufacturers is not easy. Not just Lotus but other British specialist sports cars manufacturers find themselves between a rock and a hard place unable to go back or climb out.

FI has the means to keep the brand in the forefront of prospective purchasers but this really requires success and is expensive so much so that only the mass producers can afford the cost and potential loss. Chapman achieved miracles with relatively low budgets but he was increasingly aware of the need for ever increasing spend and investment in R&D

It’s to be hoped that Lotus can succeed in the current generation of FI and that this might translate into a wider purchasing appeal in the emerging markets of the East and South America etc. There has been recent talk of reentry into F1.

Learning Opportunities

Our learning /educational opportunities are intended to be challenging thought provoking and requiring additional research and/or analysis.

These opportunities are particularly designed for a museum/education centre location where visitors would be able to enjoy access to all the structured resources available in conjunction with any concurrent exhibition.

In this instance we suggest the following might be appropriate: –

- See listing for recent articles focused on Lotus through the 1950’s

- Produce a spread sheet directly comparing and contrasting L.Bond /C.Chapman

- To what extent do you believe the Berkeley “Hull” body chassis informed Chapman and his concepts for Lotus Elite and Type 25

- Debate the sustainable elements of Chapman and Bond car designs, how why and what means might the principles we reinvented for today?

Education, Entertainment, Exhibitions Economics

The proposed museum believes that commercial considerations are both necessary and complementary with its educational objectives.

For these reasons our Business Plan includes provision for promoting products and services which share Chapman’s ideals of mechanical efficiency and sustainability. In addition, we propose merchandising that explain and interprets the social and cultural context of Chapman’s designs in period. It’s suggested there will be catalogue for on line purchasing.

Consistent with the application of benchmarking is a series of exhibitions based on the display and evaluation of Colin Chapman/ Lotus and their main competitors. This might take the form of contrasting marque histories, competition, and design construction and assembly methods. Noting how history and changing assessments and perceptions impact on marketing etc.

Cars and design objects can be placed in juxtaposition for maximum interpretation value. In addition, test runs and other photo opportunities can be exploited.

Merchandising opportunities are extensive.

Cooperation with marque owner clubs and manufacturers museums could be sought.

This provides some exciting opportunities because of the extreme contrasts not least visual in many cases. In addition, it allows the proposed museum to examine an important and continuing manufacturing activity so desperately needed which embraces a British success and continuity.

An exhibition and interpretation of this nature also permits vivid graphic and practical demonstrations of sustainability in the more considered holistic context.

- Special Bond: Joined with Triumph

- Bond ties a knot

- Bond Link

- Bond United

- Bond’s Liaison

- Bond: A certain chemistry

- Instant Bonding

- A Bonding Agent

- Bonds across the generations

- Bond’s link with Lotus

- Bond forms a Union

- Bond A real attachment

- Bonds binding agreement

- Bonds a real investment opportunity

- Bonded Together

- Bond Bona fide

- Equipe: Stocks and Bonds

- Bond’s Brave New World

- Conclusion : Bond’s Brave New World

Figure 6.Note prices and cross reference with A&R articles on relative prices etc.

The Commonality between Chapman and Bond includes: –

Both were: –

- Engineers and Industrial Designers

- Had aeronautical experience and used design principles extrapolated into their cars

- Entrepeneur’s with their own brands

- Manufactures of road and competition cars if at very different levels and volumes

- Racing drivers but again of very different ability

- Worked in conjunction with other major suppliers i.e. proprietary engines

- Competed in Formula Junior

- Provided consultancy and diversified their product range

- Did a great service to British motoring and motor racing in critical post war period

- The Elan+2 and Bond Equipe competed for similar audience

- Books have been written on both

- Their designs at differing levels addressed fuel efficiency and sustainability

- Both have a significant legacy and Car Clubs that advance knowledge on their respective Brands.

- Subject of quality biographies

Both men and their brands did a great serice to Britain in the post war era.

Both were entrepreneurs and applied their skills, creativity to producing products that were in demand.

Both increased morale and particularly in Chapman’s case increased Britain’s engineering reputation onto an international level.

Laurie Bond although not as glamorous brand as Lotus is significant and his “Hull” chassis body chassis unit might he influenced Chapman more than generally credited.

Chapman’s products were more suitable for export and as such both men through the manufacturing created employment whilst providing the nation with leisure, transport and competition machinery.

In the editor’s estimation this achievement ranks with those industrial designers who are possibly better known in furniture etc.

It’s worth noting that although Bond does not have dedicated museum the Bubblecar Museum features many examples of his work [ see A&R article on Berkeley]. This does not apply to many of the largest quality manufacturers willing to invest, promote their brand, its identity and historical reputation.

Using the comparative analysis that the A&R adopts it’s hoped that the merit of Colin Chapman and Lotus are seen as equally worthy of a museum. As such the investment is intended to: –

- Promote Car sales and engineering

- Contribute to national economy through tourism

- Support and integrate with local economy to support enriched tourism within the experience economy

- Contribute to the development and education of engineers and entrepreneurs

- Reduce welfare by increasing education and self-sufficiency and skills

- Promote the wider cultural dimension of design through engineering

The editors are developing a series of comparative articles that will evaluate Lotus against: –

- TVR

- Ginetta

- Gilbern

- Elva

- Chevron

- Reliant

- Turner

- Marcos

Please let us know if you would like other marques to be included and any preference in sequence.

Appendix 1: Fibreglass from wiki

“Ray Greene of Owens Corning is credited with producing the first composite boat in 1937, but did not proceed further at the time due to the brittle nature of the plastic used. In 1939 Russia was reported to have constructed a passenger boat of plastic materials, and the United States a fuselage and wings of an aircraft.[7] The first car to have a fiber-glass body was a 1946 prototype of the Stout Scarab, but the model did not enter production.[8]

During World War II, fiberglass was developed as a replacement for the molded plywood used in aircraft radomes (fiberglass being transparent to microwaves). Its first main civilian application was for the building of boats and sports car bodies, where it gained acceptance in the 1950s. Its use has broadened to the automotive and sport equipment sectors. In production of some products, such as aircraft, carbon fiber is now used instead of fiberglass, which is stronger by volume and weight.”

Appendix 2

See wiki:

3-wheel vechicles

Micro cars

Cars introduced in 1949

Reference:

Websites:

My word is my Bond:-

http://bondcars.net/Scooters.htm

www.Lotus.com

Books

A-Z of Cars of the 1970’s. Robson. Bayview.1990.

ISBN:1870979117

A-Z of Cars 1945-1970.Sedgwick & Gillies.Bayview.1986.

ISBN:1870979095

Racing Cars of the world. Roberts.Longacre.1962.

The Racing car. Jenkinson. Batsford.1962.

The World’s Racing Cars. Armstrong. Macdonald.1959.

British sports cars. Watkins. Batsford.1974

ISBN:0713404728

The Sports Car. Boddy. Batsford.1963.

European Sports > Cars. Robson. Foulis.1981.

ISBN:085429281

Observers Automobiles. Manwaring. Warne.1965

Motor Sports Car Road Tests. Temple Press.1965

The Lotus Book .W.Taylor.Coterie Press.1999.

High Performance Cars. Autosport. [Morgan with a difference –John Bolster- TOK 258]

Motor Sports Car Road Tests Second Series. Temple Press.1965

Guide to Used Sports Cars Vol’s I &II.J.H. Haynes. Haynes.c 1965

Lotus –The Legend. David Hodges.Parragon1998.

ISBN: 0752520741

Researched at British library:-

Lawrie Bond :Microcar Man.Wortherspoon.Pen&Sword.2017.

ISBN:9781473858688

Figure 7. Recent biography

Lawrie Bond.Wotherspoon.Bookmarque.1993.

ISBN:1870519167